Over kedgeree and a cool, crisp Gavi di Gavi at The Delauney, the country’s foremost court artist explains why she welcomes cameras in court even though it could put her out of a business, and reveals secrets from the trials of the rich and famous.

Over kedgeree and a cool, crisp Gavi di Gavi at The Delauney, the country’s foremost court artist explains why she welcomes cameras in court even though it could put her out of a business, and reveals secrets from the trials of the rich and famous.

Texan-born Priscilla Coleman has had a ringside seat at the most high-profile and infamous cases of the last three decades.

Her oil pastels and water-based sticks have documented the trials of serial killers and celebrities, including Rosemary and Fred West, Ian Huntley and Maxine Carr, Barry George, Harold Shipman, Rolf Harris, Dave Lee Travis and Max Clifford.

The Wests, she recalls, didn’t look evil, just ‘ordinary’. Publicist Max Clifford, convicted of indecent assault under Operation Yewtree, she describes as ‘happy-go-lucky’. while DJ Dave Lee Travis, convicted in the same operation, teased her for making him look like Rolf Harris.

While fellow artist Harris, she says, was very friendly and even signed one of his books for her while he was in the court café. But, in the witness box, she says, he ‘could be pretty angry and bossy and looked quite fierce’.

In the phone hacking trial she compares Rebekah Brooks to Botticelli’s painting of the Birth of Venus, with her ‘high forehead, angel lips and mane of red hair like a Pre-Raphaelite model’.

Brooks, who was cleared of all charges, recalls Coleman, was ‘dignified, held herself tall and straight and was usually always controlled, except when she broke down in the witness box.’

Coleman witnessed part of the secret trial of Enrol Incedol, which she describes as ‘really weird’ and at the other end of the spectrum Gillian Taylforth’s unsuccessful libel case against The Sun, the Hutton inquiry and the inquests into the deaths in the July 7 bombings.

In her long career, those who have stood out include Christine Hamilton, wife of disgraced former Tory MP, Neil Hamilton. During his unsuccessful libel action against Mohamed Al-Fayed, Coleman recalls how ‘Christine Hamilton was shooting daggers the whole time at George Carman QC [who represented Fayed] and Al-Fayed’.

While she was charmed by supermodel Naomi Campbell, during her successful 2002 privacy action against Mirror Group Newspapers. ‘She was gorgeous – such a pretty girl, but she was really naughty’ airing her opinion of the newspaper’s barrister, Desmond Brown QC, in tones not so sotto voce that her views went unheard by those in court.

Beatles star Paul McCartney also won her over. Though the proceedings were closed to journalists, Coleman sat outside the court. McCartney and his ex-wife Heather Mills went in through separate doors, she recollects. ‘He walked through the door like a gentleman and greeted people, but he seemed very sad.’

While Mills, Coleman recalls ‘was a real contradiction and seemed happy with the attention, even though some of it was not very nice.’

After discovering what had gone on in court, Coleman produced this sketch of the moment Mills doused Macca’s solicitor, Fiona Shackleton, with a pitcher of water.

But it’s not all about the A-listers. ‘Judges and lawyers are fun to sketch and fun to listen too – they are always full of surprises’.

The late George Carman QC, who bought some of her pictures, she remembers especially. ‘He was mesmerising, flamboyant, naughty and always full of surprises.

‘He was a showman – similar to how lawyers behave in the States. It’s kinda frowned on now to be like that here, but it’s more entertaining’.

From the bar, Coleman also singles out the ‘charming’ Orlando Pownall QC and Courtenay Griffiths QC. Of the latter, she notes ‘he also has a little bit of an American style. And he charms jurors a lot. He’s really charming and that is so important as a barrister, particularly a criminal barrister’.

Having recently sketched the Hatton Garden robbers, she says how ‘nice and sweet’ the sentencing judge, His Honour Judge Kinch QC, was. ‘All the other judges were really jealous of him; they all wanted that case,’ she adds.

His Honour Judge Drake, who presided over several high profile defamation cases in the 1990s, she recalls with fondness. Attending an often crowded court 13, he would allow her to sit on the steps leading up to his dais.

‘Some judges are so strict it feels like torture, but when you meet them, they are often really nice,’ she says, adding that the clerks can be fiercer than the judges.

In 2013 Coleman made legal history becoming the first person in almost a century to be allowed to sketch inside the Supreme Court, despite the fact that filming has been permitted in the country’s highest court since 2009.

She studied fine arts and graphics at Sam Houston University in Texas and then worked for advertising agencies and a printing company, before getting into court sketching.

Coleman got her first gig when her college professor recommended her to cover a big case for the television news in Texas, because she liked to draw quickly.

‘Two police officers had thrown a Mexican guy who was really drunk and wearing army boots into the Buffalo Bayou. He drowned and they were charged with murder’.

Though initially she had little idea what to expect, after that case, she got the bug.

In her early years working in Texas, Coleman drew prisoners being given lethal injections, from accounts given to her by her cameraman and other witness, as she never attended an execution.

Married to an English banker, Coleman crossed the pond in the 1980s. ‘I had my tape with all my work on, but I didn’t know how things were done in this country. I went to ABC who told me that most of their graphics were done in New York and they didn’t need a court artist.

‘So I thought I’d go to the Old Bailey. There was a big trial there – a child abuse case where the parents had killed their little girl. A couple of reporters were outside doing a piece to camera. One looked a little bit grouchy, but the other, Simon Cole, who worked for ITN, looked friendly.

‘I spoke to him and he told me to go and see his news editor, who liked my work and sent me to cover another case at the Old Bailey.’

The second case she covered was the 1986 Jeffrey Archer libel trial. ‘It was just wonderful,’ she recalls, ‘so exciting’.

In the States you can go in to courts and draw at will, but doing so here is banned, due to a 1925 law – section 41 of the Criminal Justice Act to be precise.

Coleman learned that the hard way. ‘I had my notebook and I was doing little tiny drawings in the Archer libel case. Someone in the public gallery told the court clerk and I got in trouble for it. She took me out and said I could have been fined me’.

Taking out her notepad, Coleman explains how she works. ‘I take written notes – names, arrows, directions, colours. It’s like studying for a test and making things stick in my mind’.

Her shorthand aide memoir helps her draw at speed, which is crucial as she sometimes has as little as five minutes to complete a sketch in time for the news bulletins or print deadlines.

And her working environment can be hit and miss. While there are long tables in the corridors of the Royal Courts of Justice, she is often forced to sketch al fresco — in the car park at Belmarsh, where everyone is kicked out as soon as the court rises; on the grass outside Southwark Crown Court, and even on a bench in a graveyard.

‘There used to be a sofa in the ladies at the RCJ – I’d sit in there and work. PA’s (Press Association) room is pretty good, but they’ve got quite a big crowd in there and all the tables are taken.’

Coleman published a selection of sketches from some of the most famous cases, in a book, Court Scenes: The Court Art of Priscilla Coleman, written by the Evening Standard’s pre-eminent former court’s correspondent, Paul Cheston. The duo are set to publish a second volume later this year.

But capturing the scenes is not always easy. First off, getting a seat in court can be a scramble.

‘They make it so difficult for even me to go in. For the Adam Johnson trial I had to get up at 1am to stand in a queue, because it was first come first served for the tickets and there were only eight places’.

When she does get in, the views can be limited, because of where she has to sit, court furniture obstructing her view or security measures that restrict visibility.

She recollects a time at the Old Bailey, where she was supposed to sit in a position from where she could not see the defendants.

Coleman suggested she bring in a couple of bookshelves from home for her and the other two court artists to sit at, so they could see. She was given permission and brought in the shelves strapped together with gaffer tape.

‘When we weren’t there the solicitors used them. I thought they might be needed again, so I left them there. I think they’re still there — in court 12, I believe. And I’m missing two book cases.’

Public access to the courts, she bemoans, is getting worse. ‘It’s not because the courts are old – the modern courtrooms are worse than the old ones. The design of them is pretty bad’.

She is particularly annoyed by the changes made to several courts up north, where she complains that reflective glass has been used as a security measure to prevent members of the public from seeing the jury, resulting in observers being unable to see the person in the dock.

‘Somehow they have decided that the public are really dangerous and they don’t want them to see. They are afraid they will intimidate jurors.

‘So you only get a glimpse of defendants when they walk in and out, but that’s it – it’s pretty bad’.

On the positive side, she thinks that court 1 at the Old Bailey is ‘pretty good for general all round letting people see’.

She suggests courts should be built ‘on the model of a church where everyone can see the preacher’. At present, she says: ‘It’s like courts are kinda open, but not really’.

The increased use of cameras in court, she hopes will improve things. And she is pleased to have been asked for her opinion. ‘No one ever thinks to ask me about it when it’s being debated,’ she says.

Cameras have filmed the Supreme Court since 2009. Judgments from the Court of Appeal have been caught on camera since 2013 and a pilot filming judge’s sentencing remarks in six crown courts will begin soon.

‘I’ll be put out of business,’ she predicts, judging by the American experience where court artists have become ‘unusual and kinda rare’ due to televised hearings.

But she is concerned that filming must be done well. Good examples, she says, are the trial of Oscar Pistorius – ‘they got some pretty good shots there’ and the House of Commons, where ‘they have really worked at it and done a wonderful job – it’s beautiful.

‘If they could do it like that in the courts, they would be doing a really great job’.

Even in the States, where trials have been filmed for some time, Coleman notes ‘they get some really crummy camera angles’.

At other times, the technology can be too good. ‘I saw a trial on TV with subtitles instead of sound. I was told they couldn’t use the sound because it was too good and picked up all of the comments that the lawyers made to each other’.

A long-suffering aficionado of court IT, she makes a plea for the technology to be better than the kit used to relay hearings via videolinks into media annexes.

The quality of the video link in the hacking trial, she says was poor. ‘The screens showed fuzzy black and white images. You couldn’t even see one of the defendants and the sound was not good.

‘When you can get great shots on a mobile phone, I don’t understand why they couldn’t have done this better. It was a very important case. I guess it all comes down to money.’

Another gripe is the numerous rules about what she can and cannot portray – an art made harder by the fact that the rules are unwritten and inconsistent. ‘They make it so hard. I don’t know if they realise or care.’

The definite no-nos are that: you cannot show children; you can indicate their presence, but you cannot show the jury and, where identity is in issue, you can only show the back of a defendant’s head.

Other issues are a matter of taste. For instance, although she drew a picture of the bath tub exhibited in the trial of Ian Huntley and Maxine Carr in relation to the deaths of schoolgirls Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman, he did not publish it.

During that trial, the judge, Alan Moses ruled that no interactions between Carr and Huntley, that the jury might not have seen, could be depicted.

And during the trial of Barry George for the murder of TV presenter Jill Dando (his conviction for which was subsequently overturned), drawings had to be shown to the judge and barristers before publication and for while they were only permitted to depict three-quarters of his face.

While the pictures drawn during an Old Bailey trial of Real IRA members had to be oked by the defendants themselves. ‘Their barristers didn’t want them to be portrayed in a bad way, looked guilty, with a five o’clock shadow or a grouchy expression’.

With some frustration she harrumphs: ‘They never really go all the way and give you everything, yet the court proceedings are public and anyone can walk into a court and try to see what’s going on, providing there’s room’.

Therein lies another problem that she thinks cameras would solve – the lack of space in many courts for the press and public to attend. ‘In the trials that the public will want to see there will not be room for them to fit in the court.

‘A lot of times even reporters get stuck outside and have to rely on PA when their publication might want a different angle. Having cameras in court would solve that.’

She continues: ‘I would hate to prejudice a trial, but they should just get over it. If the judge and jury can hear and see something, let everyone.

‘You can’t keep a secret anymore with the internet and social media; people are always tweeting and gossiping’.

Coleman thinks cameras should bear all about what goes on in courts. ‘Just put it all out. Stop trying to be secret all the time; it’s not going to work.’

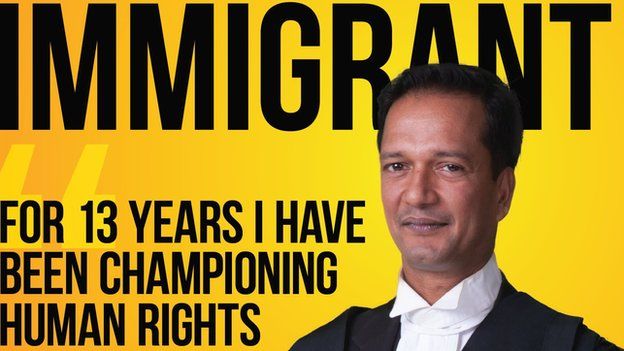

In a profession that in the eyes of many remains synonymous with pale, stale, conservative, public school chaps in dull suits, Chelvan stands out from the pack – loud and proud.

In a profession that in the eyes of many remains synonymous with pale, stale, conservative, public school chaps in dull suits, Chelvan stands out from the pack – loud and proud.